Preview: Thursday 19 October 2023 (6-8pm)

Exhibition: 20 October – 25 November 2023

Press Release

Artist Video

PDF catalogue of works

Look into their eyes, you see us in them.

Their gaze is lost in themselves.

They don’t feel, but make you feel – you’re left on your own.

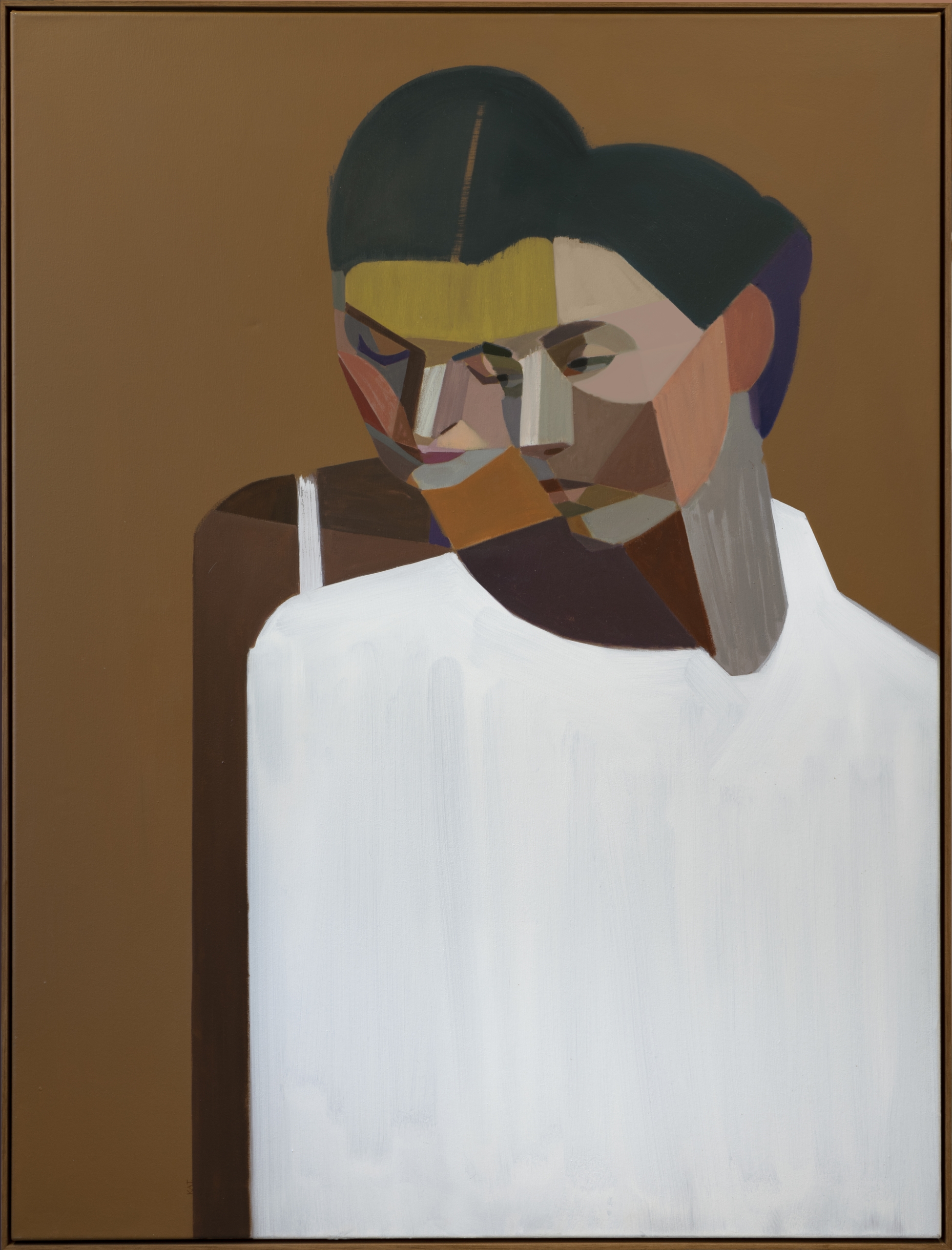

Lines, colours, shapes, geometry, cold gazes, warm emotions.

A world exists within us, within them. In each other, we see life.

You look at me, and you see them in yourself. Is life an illusion after all?

– Kat Kristof

__

In Luigi Pirandello’s cathartic text, One, No One and a Hundred Thousand, the narrator stumbles upon a paradox: the ‘self’ that each of us, as individuals, claims to know about ourselves is never totally congruent with our identity as perceived by others. He suggests that identity is not fixed but rather a fluid and multi-dimensional construct influenced by social contexts, personal experiences, and even the presence or absence of others.

…you can never know yourself as others see you. And of what use is it, then, to know one’s self for one’s self’s sake? You may even come to the point where you will no longer be able to understand why you must have that likeness that the mirror gives you back.

To entertain this philosophical dilemma is to accept that our notion of self is fragmented; that identity is never fully formed, and – possibly – the versions of us that others know are never really who we are. Does identity depend on how we are viewed by others? Or is it like a puzzle that we ourselves need to resolve?

The work of Hungarian-British artist Kat Kristof, is similarly concerned with this very incalculability of self. For Kristof, however, the ability to understand the self becomes an internalized process. She states: “In my works, most of the time it is the same person watching themselves, from outside, trying to see their true self… We are constantly de/constructing and re/constructing our spaces, identities, memories.”

She believes that through her processes, (alone, meditative, in studio) the individual experiences a more introspective understanding of their own identity, free from external influences and social constrictions. Where Pirandello’s premise suggests that the idea of self involves a complex interplay between the individual’s perception of themselves and the way they are perceived by others, it also seems to emphasize the fluidity and subjectivity of identity.

For centuries philosophers, writers, and artists have attempted to dismantle our concept of Self. From Descartes (‘I think, therefore I am’ to Freud’s Id, Ego, and Superego. Or consider Picasso’s developments with analytical cubism to, say Cindy Sherman’s exploration of the multiplicitousness (and evasiveness) of identity.

So too does Kristof ponder these grand, philosophical questions. In discussion, Kristof states: “Permanence is an illusion,” and with respect to her paintings, she asks: “Where is the outline of one’s self beyond the physical body? If I stand close to you, am I part of you? If we touch, our beings intersect, where do I start and do you begin? Do we share a single being between us?”

To consider Oscar Wilde’s sentiment that “every portrait [is] a portrait of the artist, not of the sitter”, we might assume that each painting is as much a self-portrait of Kristof as it not. Or perhaps these paintings are both self-portraits and portraits of others; one can probably imagine her substituting physical features with her own when convenient. This impermanence on the canvas is as much a painter’s technique as it is a metaphorical concept: each figure hybridized, idealized, and fragmented.

These figures seem entangled in their stream of thoughts and emotions. They fail to engage with us the way we aspire to engage with them. But to look beyond the surface of the canvas is an attempt to understand Kristof’s thought processes between developing an image and a sense of identity. The figuration is heavily stylized, reduced to indistinct forms and geometric lines, and in this sense of anonymity (given that any largely definable characteristics seem to be removed), the artist is opening the possibility for us to supplant our own ideas. Even the colour palette of greys, sepias, and opaque whites seems telling. The decision to restrict their environment seems to incur a psychological space.

For viewers, this might function almost like a Rorschaech test, in that every viewer will extrapolate their own information from the work. Whether spotting a likeness (to Kristof herself, or to a friend, a lover, a relative) or to a less specified but no less powerful register of emotions, memories, or feelings. These paintings then, do operate as mirrors. They are, as Pirandello suggests, different for each of us. Their meaning respective to each of our personal histories. When we look at them, perhaps we are learning more about ourselves, too.