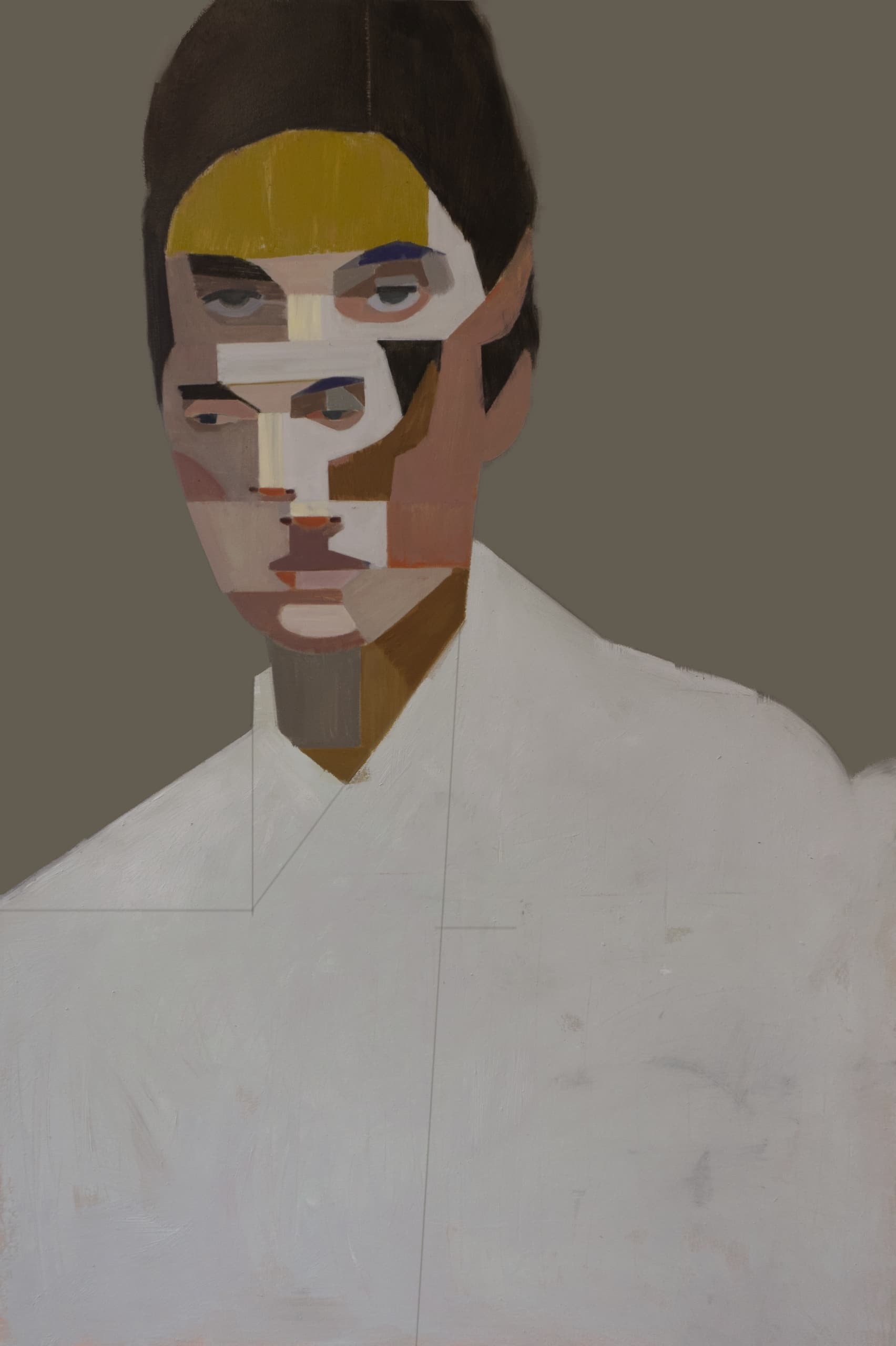

When we view Kat Kristof’s work, a few things become immediately evident: fragmented female forms that are partway through de/re-construction; a sort of shifting perspective in space in time similar to that of Analytical Cubism; and a reductive style that distills forms into shape and line. After training as an architect and interior designer in her native Hungary, Kristof, and her young family relocated to the small British town of Folkestone, Kent, where the artist decided to dedicate her aesthetic sensibility solely to her painting practice.

The persons she paints are archetypes: she and her and they. Generic and stylized, appropriated from the internet or editorial photography. Stripped of most defining features, Kristof is able to question the broad truths of those she paints. “One is me looking at another me,” she states, “questioning their feelings and thoughts.” And similarly, as viewers, we sense this sort of analytical air – both in their states of looking (or being looked at) and the tension and a ‘negative’ albeit psychologically dense space she creates around these figures. It isn’t difficult to create this imagined communication with her figures. Their eyes, downcast or in direct confrontation, seem to house myriad thoughts and sentiments. But there is a fragility in Kristof’s handling; a pausing of time and space not dissimilar to Bracques or Picasso in their adoption of multiple viewpoints and angles to portray an individual. But Kristof seems to utilize this to depersonalize her subject as if this person is anybody… or everybody.

Kristof manages to remove the sense of self, or Ego, and suggests that beings are in constant flux. And this de-personalization is also related to space and time. She states:“ These works serve as a reflection on the ever-changing nature of identity, emotions, and the physical body, exposing the unimportance of [our] perceived significance in life. [I am] intrigued by the underlying essence of nature, the consciousness that brings order and tranquility by redirecting our focus away from the thoughts of the mind and into the present moment.” Kristof’s handling of her subject matter also reifies this depersonalization, through dynamic but often vague brushwork. Turning defining characteristics into swathes of paint and colour. But it is precisely this lack of specificity that allows us, as viewers, to connect with these figures on an intuitive, emotional, or psychological level. She, her, and they become us, all of us.